∃ Convex Human A blog on computational and abstract ideas

Functional Programming

So you have decided to learn functional programming, great! You visit the first website, read a book, watch a video, and maybe listen to a podcast; when suddenly you realize that functional programming is a completely different kind of programming. That it is a fundamental change in the way you see and interact with computer programs. And maybe it’ll even require you to almost forget about everything related to computer programs!

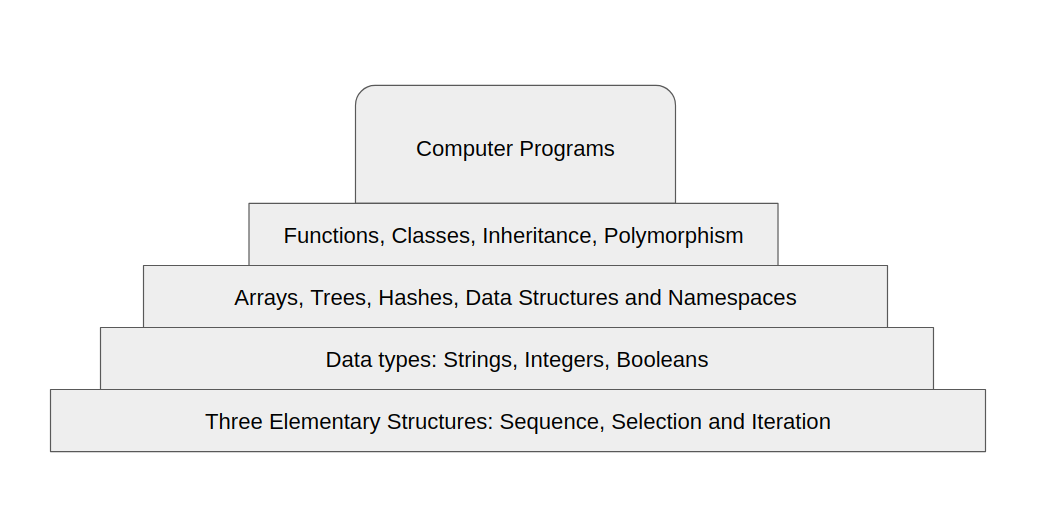

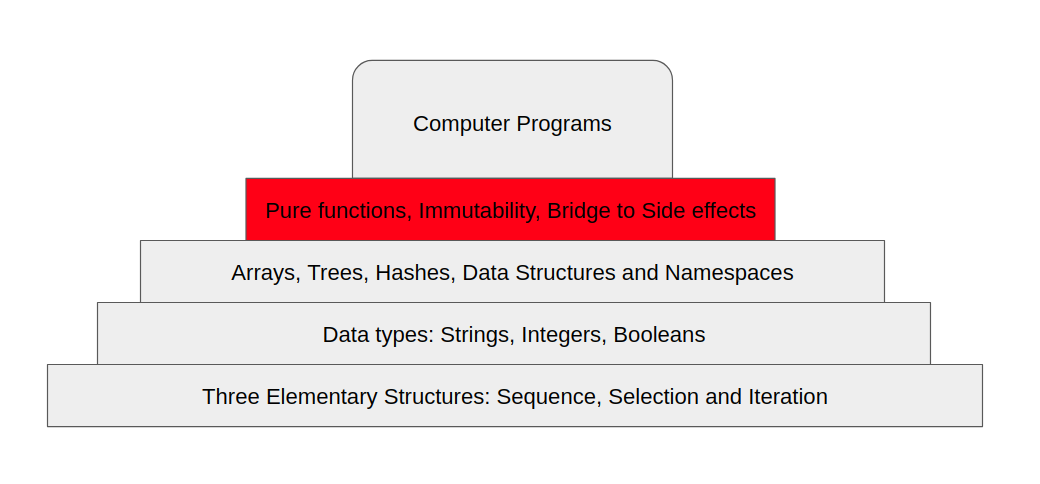

But what do we know, as programmers, so that we forget? I’ll assume that you’re coming from an object-oriented background, and if so, we can summarize the basic components of almost any program -that is, on a higher level- in the following chart:

So instead of forgetting about everything we know, how about we rebuild our idea on programming and what it means, and how it is constructed.

Three Elementary Structures

In 1966 a paper by Corrado Böhm and Giuseppe Jacopini, 2 great computer scientists, introduced the Böhm–Jacopini theorem [1] or the structured programming theorem. This theorem states that all programs can be constructed from just three structures: sequence, selection, and iteration.

So based on that, we definitely will have to have these three elementary structures in any functional program. Of course, we’ll also have data types; strings, integers, and booleans are all fundamental in the way we develop programs. Add to this the more advanced data structures like arrays, trees, hashes, and so on.

Turns out the only level of the programming pyramid that we need to rebuild, are the ideas that were brought by the Object-Oriented Programming paradigm. We need to find a more “functional” approach to doing programming.

Mathematics and Abstractions

One of the best places to go to when you want to look for a new paradigm of programming is Mathematicians! Mathematics and Computer Science share the same characteristics in problem-solving techniques, formulating and modeling problems, and a lot more. But most importantly: Abstractions.

You might remember that moment when you were trying to build this complex system, and you’re having this abstraction of the system as a model, and then this other abstraction and the other and so on, all that combined together make up this functional goal of the system. Turns out, mathematicians share the same problem as us! They’re also trying to keep in their mind an abstraction over the other to derive this “functional” goal of a mathematical model. So, what did mathematicians use that we might find useful? Functions.

Mathematical Functions

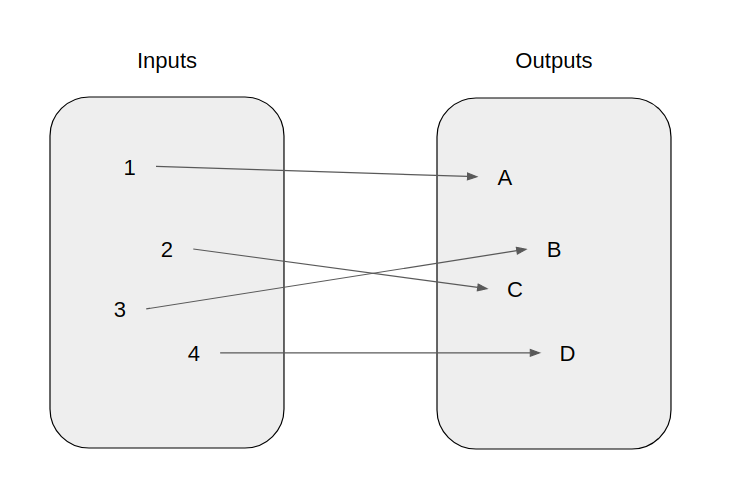

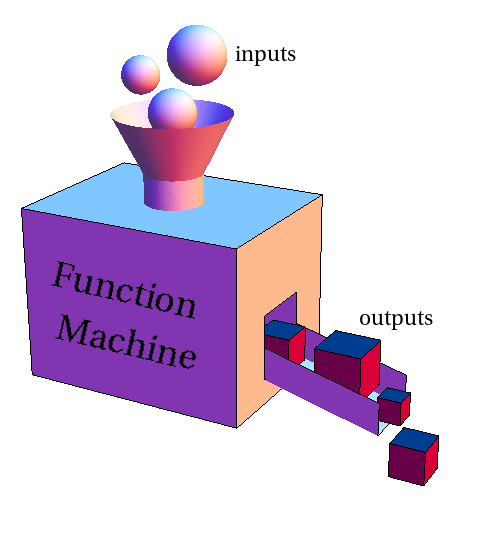

If you are a programmer you have probably heard of functions (maybe methods, routines, etc.), but mathematical functions are not the same. In mathematics, a function is a relation from a set of inputs to a set of possible outputs where each input is related to exactly one output [2]. We can view a function as a machine that can take an object and turn it into (or map it to) a different object, this is called the function machine metaphor [3].

Mathematical functions are different than programming methods/routines because of a very important thing and that is the mechanism of how they work. A simple ruby method can do a lot of things including updating the database, creating new files, sending emails. A mathematical function on the other side does only one thing and one thing only. Every input is mapped into the exact same output each time that function is called. So it’s not like f(x) is gonna be 24 today, and then 3 days later it’s 77.

So what if we borrow these ideas from mathematics and apply it to programming, in hope that our functions (programs) are easier to read and to write? There are a couple of rules and conditions that we have to follow in order for our functions to be “pure”.

Rule #1: Functions as values

A fundamental rule is that those mathematical functions are considered to be “values”. This is what we call a 1st class function [4], and they’re actually in many programming languages (that are not even purely functional). If you look for example on this ruby code:

fn = lambda { |x| x + 2 }

puts fn.(2) # = 4

As you can see, we defined a variable fn that holds a function that takes an input x and returns x + 2. Nowadays, if you look over the documentation of almost all programming languages, you’ll find the idea of pure functions developed and utilized. A function is a value that can be defined and passed as an argument and manipulated just like other variables.

# A function `add` that takes a function `fn`

# and a number `a` as parameters, applies

# `fn` to `a` and adds the result of

# `fn(a)` to `a` again.

def add(fn, a)

fn.(a) + a

end

fn = lambda { |x| x + 2 }

result = add(fn, 2)

puts result # = 2 + 2 + 2 = 6

Rule #2: No Side Effects

The second most important rule for our functions to behave purely is to behave exactly like mathematical functions do: Take an input, produce an output. That is, without any side effects.

But, what are side effects?

# A side effect

File.open("log.txt", "w") { |f| f.write "#{Time.now} - User logged in\n" }

Side effects are basically the change of the “outer” state of the function. A change that is outside the scope of the function’s inputs and outputs. Anything that deals with IO, or any external resource is considered to be a side effect. But what are our programs other than side effects?

So we need this bridge that connects our functions with the actual events and side effects that we want to do. The solution to this problem has been implemented differently in different programming languages, and we’ll take a Clojure look at that.

There’s also a huge discussion nowadays on reactive functional programming (bonus: Elm [5] is a compellingly beautiful example of that), where they deal with a lot of state change and UI elements in a functional way.

A Bridge to Side Effects

Atoms

An example on this bridge that the programming language Clojure has taken is what they call an Atom. An atom is the closest thing that someone can find to a mutable state. It is Clojure’s way of bridging the clean organized functional approach with the messy world of side effects.

Here’s how we define an atom in Clojure:

(def x (atom 0))

And then to change the value of this atom, you just throw it into a function that applies the function on that atom, and returns the value of the applied function as the new value of the atom. For example here’s how you can increment an atom:

(swap! x inc)

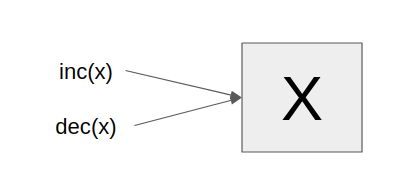

What this does is that it takes x and applies inc(x) and swaps the current value of x with the returned value of the applied function.

Now the beautiful thing happens when two threads are trying to update x at the same time.

Here, inc(x) and dec(x) both come at the same time, and they see the current value of the atom X. What happens is that this atom runs the function and notices that the value of X has changed and what happens? It runs the function that came last again.

Agents and Actors

Okay, what if I want to update a file or a database or something that is completely outside the scope of the program I’m dealing with? Here comes Clojure’s agents.

In that you basically send these side-effects into a queue specified for doing these tasks, and all of them run synchronously. The topic of agents is huge and shall be discussed in a separate article.

Rule #3: Immutability

Based on the previously mentioned rule #2, our functions should behave purely and with no side-effects. But what if our variables are mutable? That is, its state can change. You find yourself back at the problem of side-effects! So to ensure that side-effects are completely demolished we need one more important rule: Variable Immutability.

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = f(x)

# what is that value of x at this point? x!

Notice that even if you make y = f(g(h(...(x))) , the value of x is still going to be the same. Nothing is changed! f(x) takes a copy of x and returns a result based on this copy. You don’t have to figure out why x’s value is being weird when it is clearly defined in front of your eyes.

But a problem arises here. y = f(x) + g(x) - h(x) / .... + f2(x), if I define y to be the result of this huge chain of functions over functions over functions, the compiler will make this copy over copy over copy. What if x was a 1-million element list instead of 3? And with every function, we make a new copy? That doesn’t sound very memory friendly.

Turns out functional languages deal with this problem in a very beautiful way: Lazy data structures.

Lazy Data Structures

Let’s have a look at this Clojure code:

;; (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ...)

(def integers (range))

This defines an infinite list of all integer numbers in a list called integers. Of course not the infinite list of integers will be saved in your memory, but instead only what you want to evaluate, gets evaluated.

;; gets first 10 integers and maps an

;; increment function on all of them.

(def first-ten-integers (take 10 integers))

(def incremented (map inc first-ten-integers))

The way lazy (or persistent) data structures are defined in memory is a very complex and interesting topic that will be discussed in the next article.

Conclusion

So taking the ideas of mathematicians into programming wasn’t very bad after all. We’ll still use the same fundamental concepts of programming, but we’ll only change the higher level way of modelling our programs. We added some rules in hope that our programs are cleaner, and more concise. But functional programming isn’t this magical box that will make all your dreams come true. You’ll still find yourself making errors, you’ll spend a couple of minutes looking for a missing bracket or to fix a simple bug. It is just a cleaner, more organized way of thinking about computer programs.

References:

[1] - Flow diagrams, turing machines and languages with only two formation rules: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/355592.365646#CIT

[2] - Function: https://mathinsight.org/definition/function

[3] - Function Machine: https://mathinsight.org/function_machine

[4] - What are first-class functions? https://lispcast.com/what-are-first-class-functions/

[5] - Elm Programming Language: https://elm-lang.org/

This article was heavily based on the work of Bob Martin and his book Clean Architecture: https://blog.cleancoder.com/uncle-bob/2012/08/13/the-clean-architecture.html and Russ Olsen’s talk Functional Programming in 40 minutes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0if71HOyVjY.

Written on December 26th, 2020 by Mohammad Alamarneh