∃ Convex Human A blog on computational and abstract ideas

Laziness and Infinity

One of the most beautiful concepts that functional programming was built upon, is lazy evaluation. Lazy evaluation is a common technique not only in functional languages but in many other programming languages as well but it’s much more efficient to do in functional languages because we know that there aren’t any side effects. Some languages are naturally lazy, and the others are only lazy when you need them to be.

But what exactly is lazy evaluation?

Evaluate only what you need

Lazy evaluation of programming expressions is a way to tell the computer to not evaluate the expression until it is called. It also ensures that the expression is not run twice for the same input (that is sometimes called memoization). There are a lot of terms for lazy evaluation, some call it call by need because you only call the function or expression when you actually need the value of it. Some others call it delayed evaluation and that’s because the evaluation of a certain expression is only delayed until you call it.

Let’s see a couple of examples on how lazy evaluation in Clojure works. No Clojure background is required to understand this, but it assumes basic knowledge of programming and computational concepts.

Firstly, here’s a list that contains all the numbers from 0 to 9 in Clojure.

user=> (def array (range 10))

As you can see, we defined the function range (range 10) which returns all the numbers from 0 to 9. But did it really run? The answer is no! this only defined that we want -sometime in the near future- to get the values returned by that function. Only if we call the defined array, will the function actually run.

user=> array

(0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9)

Lazy Sequences

The very magical thing appears here:

user=> (def infinite-list (range))

We, ladies and gentlemen, just defined an infinite list, how interesting? I know this seems surreal, but let’s have a look at how actually very practical that would be.

This is called a lazy sequence. How did that happen? How did we define an infinite list? It’s as we said because the function (range) didn’t actually get executed. It is waiting for us to call it so that it gets executed. If you call array at that point, it’ll cause an infinite loop that won’t stop.

But you can do a lot of operations on lazy sequences. For example, here’s how we get the first 10 integer numbers of the infinite list we just defined:

user=> (def infinite-list (range))

user=> (take 10 infinite-list)

(0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9)

We can also define the infinite list of even integers:

user=> (def even-ints (filter even? (range)))

user=> (take 10 even-ints)

(0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18)

Here, we defined even-ints to be the infinite list of integers - (range)- filtered using Clojure’s filter function, which takes as a parameter a function even? that checks if the number is even or not. And then we evaluated only the first 10 terms of the list, which returned the first 10 even integers.

Let’s have a deeper look on a little bit more complex example (and one that is always brought up when talking about infinite sequences), and that is how to define the infinite list of prime integers.

Infinite List of Primes

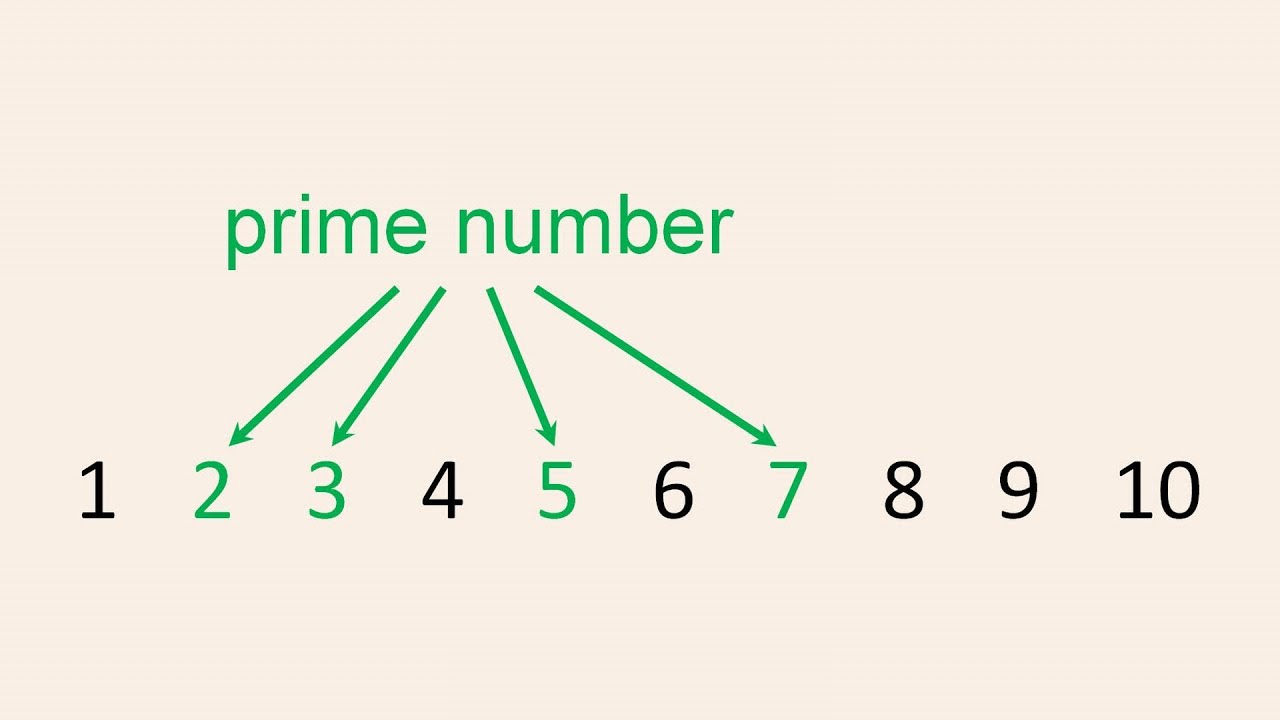

What is a prime?

A prime is a number that is only divisible by itself and 1. In other words, a number n is a prime iff the list of its factors are only [1, n].

Naive Implementation

So let’s a define a function factors that takes a number n and returns a list of all its factors.

user=> (defn factors [n]

(filter #(zero? (mod n %)) (range 1 (+ n 1))))

user=> (factors 15)

(1 3 5 15)

user=> (factors 7)

(1 7)

So this takes the list (range 1 (+ n 1)) that returns the integers from 1 → n exactly, and filters all these numbers that matches the criteria: (n mod x == 0).

Now we can define a function prime? that determines if the number n is a prime, and that would be only if the list of its factors is exactly [1, n].

user=> (defn prime? [n]

(= (factors n) [1 n]))

Now the only thing left for us is to define the infinite list of prime integers is to filter the infinite list of integers using our prime? function.

user=> (def primes (filter prime? (range)))

user=> (take 10 primes)

(2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29)

And that’s it! We just defined the infinite list of all prime integers! Look at how short (and elegant) the code is when put together:

(defn factors [n]

(filter #(zero? (mod n %)) (range 1 (inc n))))

(defn prime? [n]

(= (factors n) [1 n]))

(def all-primes

(filter prime? (range)))

One thing that remains, though, is how long does it take to evaluate the first n prime numbers? Let’s have a look:

user=> (time (take 100 all-primes))

"Elapsed time: 0.025333 msecs"

(2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29 31 37 41 43 47 53 59 61 67 71 73 79 83 89 97 101 103 107 109 113 127 131 137 139 149 151 157 163 167 173 179 181 191 193 197 199 211 223 227 229 233 239 241 251 257 263 269 271 277 281 283 293 307 311 313 317 331 337 347 349 353 359 367 373 379 383 389 397 401 409 419 421 431 433 439 443 449 457 461 463 467 479 487 491 499 503 509 521 523 541)

user=> (time (take 1000 all-primes))

"Elapsed time: 0.033803 msecs"

(2 3 5 7 .....)

0.03 msecs! That is actually really good! Note that this is the time taken to generate a lazy sequence since take returns a lazy sequence. If we want to measure the actual running time over all n primes, it would be something like this:

user=> (time (dorun (take 1000 all-primes)))

"Elapsed time: 336.496157 msecs"

This is called lazy sequence realization and it is done by using dorun (you can also use doall).

So, 300 msecs. Not so bad, but we can actually make it much better.

Sieve of Eratosthenes

A very long time ago, in the age of Greeks, there was an ancient (brilliant) mathematician who after his name (Eratosthenes) was named a very efficient prime finding algorithm that is still used to this day!

The algorithm basically goes like this:

- Define the list of all integers (up to n, deterministically, and infinitely, lazily).

- Mark the first value (Let’s call it

x) in the list as a prime. - Remove all multiples of

xby removing all the values between2x -> n. That will be(2x, 3x, 4x, ...). - Take the new list and send it back to step 2.

You can find a very funny (and beautiful) visual explanation of the algorithm here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V08g_lkKj6Q

And a more formal technical discussion, and its implementation in C++ here:

https://cp-algorithms.com/algebra/sieve-of-eratosthenes.html

Here’s the code for sieve in Clojure, defined lazily.

(defn sieve [inf-list]

(cons

(first inf-list)

(lazy-seq

(sieve (filter #(not (zero? (mod % (first inf-list)))) (rest inf-list))))))

This defines a function sieve that takes an infinite list (or a lazy sequence) and returns a list that is [ (first element of the infinite list), (sieve of the list filtered by what is not a multiple of the first element) ]. Notice that before recursively running the function, we specified for Clojure that the returning list is a lazy-seq and that we don’t want you to evaluate everything but instead only what we ask you for.

And now when we run it:

user=> (take 10 (sieve (drop 2 (range))))

(2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29)

user=> (time (dorun (take 1000 (sieve (drop 2 (range))))))

"Elapsed time: 152.715236 msecs"

And that’s almost half the runtime of the first approach!

I would like to note something that was mentioned before, and that is Clojure is not entirely lazy. The only lazy functions are map, filter, reduce, repeatedly and a couple more functions. You can also always tell Clojure (explicitly) that a list is lazy by calling lazy-seq on it.

Other languages like Haskell, for example, are entirely lazy, so by nature any returned sequence is a lazy sequence that won’t be executed until it is called.

Conclusion and Reflection

We just saw some profound power of a different and special kind of programming techniques: Lazy Evaluation. The opposite of that is usually called Eager Evaluation, or Strict Evaluation.

What I find most interesting in the idea of lazy evaluation of expressions is that you can basically ask your program to save the abstraction of the list instead of its values. You save the “formula” of a function instead of evaluating it. You separate how to generate the value — the code that you have to type in that generates that value — from when or whether you run it because you might not need to run that code. That, in my opinion, is higher-level functional programming at it’s finest.

Of course, you might think that an infinite list of primes is not that practical, and you might not need it in an actual production-level system, but you’d surprised at how practical the concept of lazy evaluation is, and how much it optimizes your code’s runtime and memory usage.

Resources

This blog is a way for me to strengthen my knowledge in a topic that I want to learn. Here are the resources that this blog post was written upon, and it would be greatly useful if you want to dive deeper in the subject and learn more.

- Clojure docs

- Being lazy in Clojure

- Infinite Data Structures: To Infinity & Beyond! - Computerphile

- Practicalli’s Lazy Evaluation

- Lisp Cast: What is Lazy Evaluation?